This post is co-written with Rutger University - Newark professor of economics Jason Barr and published jointly on his Skynomics Blog.

“Those sickened must be cured or die off, & being cheifly[sic] of the very scum of the city, the quicker [their] despatch[sic] the sooner the malady will cease.”

John Pintard, a founder of the New York Historical Society and a former secretary of the New York Chamber of Commerce wrote these words to his daughter on July 13, 1832. New York City’s first great cholera epidemic had begun just two weeks earlier. The outbreak continued through September and 3,500 cholera deaths were officially recorded within the city. In just three months, 1.5 percent of New York City’s population died from the disease.

Pintard’s crass words matched the feelings of many 19th-century upper-class New Yorkers. For Pintard and others like him, illness from infection, particularly cholera, was a sign of moral turpitude. Those with an upright character were protected from ghastly contagions. In another letter to his daughter, Pintard stated these feelings explicitly: “At present [cholera] is almost exclusively confined to the lower classes of intemperate dissolute & filthy people huddled together like swine in their polluted habitations.”

Figure 1. Location of Officially Recorded Cholera Deaths in 1832. Source: Pulitzer Center.

In part, people of Pintard's ilk were correct in their belief of the concentration of cholera. The Sixth Ward, the location of the infamous Five Points neighborhood, contained the most severe concentration of cases and deaths as the following map of 1832 cholera deaths reveals. The large red blotch in the middle is in Five Points. Although not known at the time, cholera was a waterborne disease and spread more easily in Five Points because the neighborhood was constructed over the filled-in Collect Pond, creating poor drainage before New York fully built out its water and sewer system. That the poor immigrants were “forced” to live over former swamps and lakes was, certainly, due little to their supposed immorality or “dissolution.” It was simple finance–those in Five Points couldn’t afford to live elsewhere.

The Safety Dance

As a prophylactic, many wealthy, on the other hand, simply fled to safer and more spacious environments. As historian Charles Rosenberg writes,

A hyperbolic and sarcastic observer remarked . . . ‘fifty thousand stout-hearted. . . New Yorkers scampered away in steamboats, stages, carts, and wheel barrows.’ Farmhouses and country homes within a thirty-mile radius of the city were filled. Yet the exodus continued . . ..

However, only the wealthy could afford to escape. Rosenberg further laments, “The poor having no choice, remained.”

The 1832 cholera epidemic wasn’t the first or the last outbreak to roil New York society. Smallpox and yellow fever were persistent concerns throughout the early decades of New York’s growth. Cholera, measles, tuberculosis, typhus, typhoid fever, and other infectious diseases would continue to devastate families throughout the 19th century.

Figure 2. Source: NYC Dept. of Health.

Poverty as Vice

In the popular consciousness, Manhattan’s Lower East Side tenements became synonymous with filth, poverty, density, and disease. In 1842, Charles Dickens described one dilapidated tenement in his American Notes for General Circulation:

What place is this, to which the squalid street conducts us? A kind of square of leprous houses, some of which are attainable only by crazy wooden stairs without. What lies beyond this tottering flight of steps . . . A miserable room lighted by one dim candle and destitute of all comfort, save that which may be hidden in a wretched bed. Beside it sits a man: his elbows on his knees: his forehead hidden in his hands. ‘What ails that man?’ . . . ‘Fever’ he sullenly replies without looking up.

Jacob Riis provided the most famous descriptions of life in the tenements in his 1890 classic, How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York. Like Dickens, poverty, density, disrepair, and disease are inexorably intertwined in many of his descriptions. He describes one tenement apartment,

The family’s condition was most deplorable. The man, his wife, and three small children shivering in one room through the roof of which the pitiless winds of winter whistled. The room was almost barren of furniture; the parents slept on the floor, the children in boxes, and the baby was swung in an old shawl attached to the rafters by cords . . . The father, a seaman, had been obliged to give up that calling because he was in consumption, and was unable to provide either bread or fire for his little ones.

“Consumption,” at the time, was the term for tuberculosis.

Blaming the poor, for citywide epidemics, Riis wrote, “In the tenements all the influences make for evil; because they are the hot-beds of the epidemics that carry death to the rich and poor alike.”

Density and Disease: A Deeper Analysis

These quotes and others like them, give a sense that some lower class neighborhoods were continually beset with disease, while the ones housing the prudent and “upright” upper class were disease-free. Yet, the 1832 cholera map displayed above shows that there was clearly disease and suffering throughout the city. So, we thus need to return to the question, were the tenements really that much worse than other districts in terms of infectious disease mortality? Are the conclusions of the rich and the reformers as grim and conclusive as they suggested?

To investigate this question, we compiled data from the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), Historical Urban Ecological data set. The data set contains information on a variety of 19th- and early 20th-century demographic and health-related data, including deaths from various infectious diseases from 1868 through 1927. The data set does not include all years—in particular data from the 1918-1919 influenza pandemic is missing, as well as infectious disease data for the years 1880-1888—but it does allow for us to study broader trends across time and space.

We focus our analysis during the height of tenement growth from 1868-1910. The data is organized at the level of New York City wards, which were neighborhood demarcations used for elections of various municipal offices, such as aldermen (analogous to today’s city council members). Across Manhattan, there were 22 wards. While they are numbered in a somewhat haphazard fashion (shown on a map below), in general, the lower-numbered wards were closer to the southern tip of the island.

Death Rates

During this period, the data reveal that, on average, about 0.95% of New Yorkers died per year from infectious diseases. Although rates of death certainly varied by age (with the youngest children particularly susceptible), we can think of this as a baseline risk that each person living in the city faced. In other words, unadjusted for age, location, or time period, an individual had just under a 1 in 100 chance of dying from an infectious disease each year. However, from the historical descriptions, we would expect that certain areas had higher risk than others.

To identify these differences, we run statistical tests (regressions) aimed at identifying the New York City wards with the most risk while controlling for yearly trends (mortality was falling over the second half of the 19th century). (Data sources and results are given here.) The map below shows each ward’s death rate relative to—that is, above or below—the citywide average. The results suggest that the reformers and the wealthy scoffers did not quite have their stories right.

Figure 3. Blue indicates the ward had, on average, a lower death rate than the city average. Red indicates above the city average. White is about the same as the city average. Death Rate = total deaths from infectious disease / population. Source: here.

Across Wards

To focus on the heart of the matter, we have created a “matrix” of topologies by dividing the wards into those that contained relatively high or low density, respectively, and those that were “safe”/low-risk or “unsafe”/high-risk based on their death rates compared to the city average.

Low Density-High Risk: The First Ward

The First Ward sits at the southern tip of Manhattan. While it didn’t have the notoriety of the tenement wards for infectious disease it had the highest rate of infectious disease deaths anywhere in the city over our time of study. In the late 19th century, before the opening of Ellis Island in 1892, this ward was the literal gateway for the majority of immigrants entering the United States through New York City. It is estimated that eight to twelve million immigrants passed through the Emigrant Landing Depot, known as Castle Garden, during its time of operation from 1855 to 1892.[1]

Many of the immigrants arrived nearly penniless, and given their lack of funds they could not venture far from the landing when they first entered America. Often, they settled briefly in almshouses and boarding houses nearby as they searched for employment and more permanent housing. Unfortunately for these immigrants, our analysis suggests that the First Ward was the easiest place for contagions to multiply. Here deaths from infectious disease were 52% greater than the citywide average.

Although the First Ward receives far less attention than the Lower East Side tenements, elevated disease risk should not be surprising. During this time the travel of most immigrants was tortuous. They were stuffed in the cavernous underbelly of a ship without ventilation and, in some instances, even light. It was not uncommon for some of these steerage passengers to die from disease or starvation en route to America. Although many were inspected for disease upon arrival, some infected passengers certainly passed through the port and into the First Ward undetected. Various diseases were thus let loose to fester in the First Ward where many immigrants made their first night’s sleep.

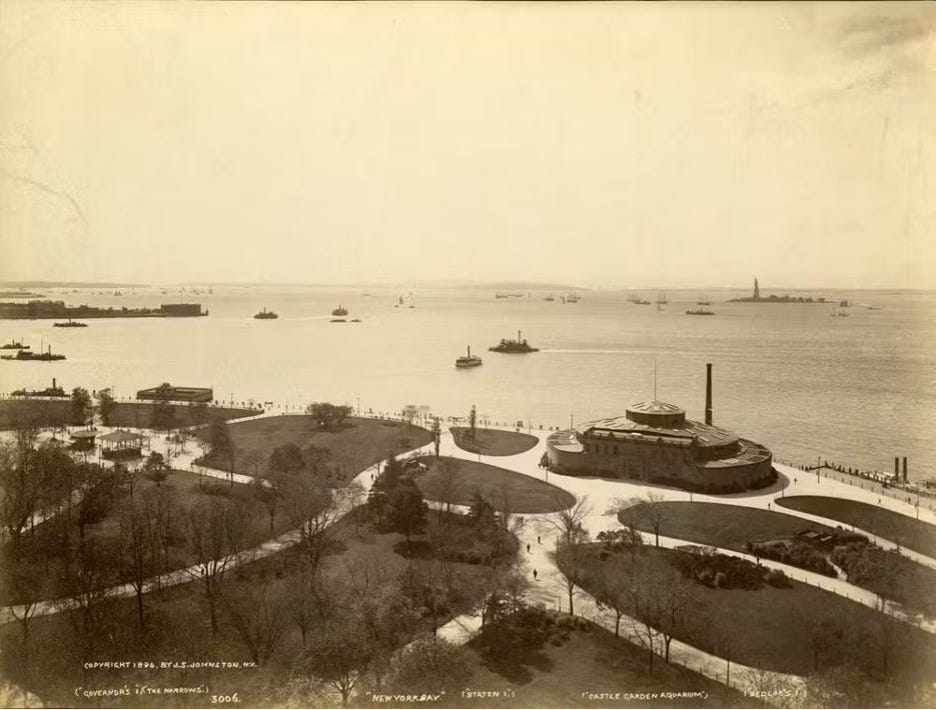

Figure 4. A photograph of New York Harbor, Governor's Island, Staten Island, and Castle Garden Aquarium, 1894. J.S. Johnston photograph collection, 1890-1899. Source: nyhistory.org.

Low Density–Low Risk

In contrast to the First Ward, the adjacent Second Ward was one of the safest in the city. It sits between the southern port and the notorious tenement districts. John Pintard, whose quote began this post, was elected an Assistant Aldermanof the East Ward (which became the Second Ward at a later date). This area was the original seat of affluence in Manhattan and home to many who made their fortunes as Manhattan's first merchants and bankers.

However, after the Civil War, this district was given over nearly entirely to industry and commerce and had few residents of any stripe. Similarly, the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Wards also contained far lower infectious disease mortality. Each of the Second, Fifteenth, and Sixteenth Wards had infectious disease mortality 16% lower than the citywide average.

Late in the 19th century, the northern wards of the city were at the heart of a great migration. As the lower wards became overcrowded, transportation options (such as the horse-drawn streetcars and later the elevated railways and the subway) allowed for faster and easier commutes from homes to places of work. Much of New York’s middle class population moved north. As they did so they skipped over the dense tenement and manufacturing districts that populated Lower Manhattan above the Second and Third Wards. Many of the affluent landed in places like the 15th and 16th Wards and other areas along Broadway, Fifth Avenue, and around such parks as Washington Square and Madison Square. Throughout this period the northern wards of the city had relatively low density and infectious disease mortality was near average or slightly below. Even the 22nd Ward, home to Hell’s Kitchen, with shanty towns along the Hudson River docks, had infectious disease risk lower than the city average.

The High-Density Neighborhoods

Focusing now on the high-density neighborhoods, we see something that is not, in fact, obvious. Some of the densest wards had infectious disease death rates that were far lower than the city average. In fact, some of the most-dense tenement districts had the lowest infectious disease mortality in the entire city. This certainly suggests that density, in and of itself, was not the great evil that reformers portrayed it to be, at least in terms of infectious disease risk.

In particular, the tenement neighborhoods of the Lower East Side had two clusters—a higher-risk zone and a lower-risk one. The higher-risk zone was located in the central wards of Lower Manhattan that included Five Points, Little Italy, and Greenwich Village. The lower-risk zone, on the other hand, was located on the east side, and included dense Jewish and German neighborhoods. In fact, in 1900, the Tenth Ward, home to many Jewish immigrants, was arguably the densest neighborhood on the planet, with some blocks having densities as high as 1,000 people per acre. Yet, the Tenth Ward had infectious disease mortality 19% lower than the city average.

The Infection Puzzle

This variance in rates of infectious disease mortality across the tenement districts offers up a puzzle. Density and poverty were not uniform predictors of disease mortality. What was going on? Why did the reformers seem to overgeneralize and misunderstand what was happening in the 19th century? We will provide the answers in Part II of this blog post, coming soon.

Jason Barr is a professor of economics at Rutgers University-Newark. He is the author of Building the Skyline: The Birth and Growth of Manhattan’s Skyscrapers. His latest book, Cities in the Sky: The Quest for the World’s Tallest Skyscrapers, will be published in May 2014. He also writes the Skynomics Blog, a blog about skyscrapers, cities, and economics.

Troy Tassier is a professor of economics at Fordham University and the author of the forthcoming book, The Rich Flee and the Poor Take the Bus: How Our Unequal Society Fails Us During Outbreaks.