Philadelphia’s problem kept growing. More people became ill every day and there were too many bodies to bury. Those who could escape, abandoned the city. Even the nurses and doctors fled. Those who remained behind isolated inside of their homes to avoid infection from the dreaded and deadly disease. Much of the city’s calamity fell upon the shoulders of Dr. Benjamin Rush. He was one of the few physicians who stayed behind but he needed help.

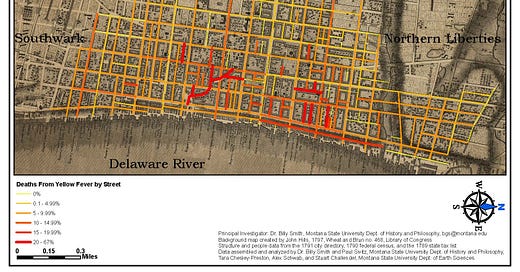

Such were the conditions in Philadelphia during the fall of 1793. A particularly potent version of yellow fever invaded the city in early August. The calendar marched forward, the outbreak grew worse, and 20,000 of 50,000 residents fled the city seeking safety. Left behind were dockworkers, laborers, and the free Black population. Many of these people lived near the docks along the Delaware River. The dampness in these neighborhoods provided the most conducive environment for the mosquitoes that spread the virus - although their role as a vector of contagion was not known until a century later. Conditions deteriorated further. There were too many people who were ill for Rush to treat by himself. He needed to devise a plan for help.

A similar epidemic had hit Charleston in 1748. Following this outbreak Dr. John Lining, wrote: “There is something very singular in the constitution of the Negroes, which renders them not liable to this fever; for though many of these [people] were as much exposed as the nurses to the infection, yet I never knew one instance of this fever amongst them…” Dr. Lining’s observations led him to believe that the Black population held immunity to yellow fever.

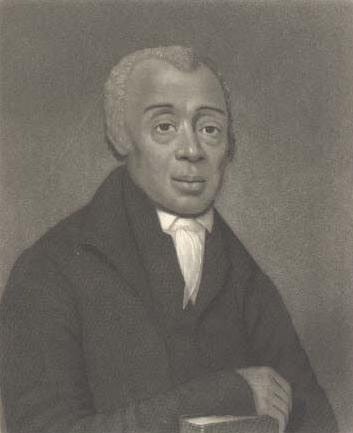

Relying on this information to be accurate, Rush called upon Philadelphia’s free Black population to come to the city’s aid. Long an abolitionist, Rush held liberal views for his time. In addition to his support of the city’s Black population, he opposed capital punishment and championed women’s education. He also had a connection to two local Black ministers in the city, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, who were co-leaders of the Free African Society. In the years leading up to the epidemic Rush had supported attempts by Allen and Jones to create new Black churches within the city, a move that was opposed by many of the white population.

Absalom Jones

Richard Allen

To recruit aid workers, he approached Allen and Jones. Based on his knowledge of Lining’s writing, he suggested to them the possibility of immunity and also enticed them with the idea that their aid may engender goodwill for the creation of the new Black city churches they long desired.

Rush’s appeal worked and the free Black population turned out to assist him. The number of Black aids was so great that Rush wrote to his wife Julia at the height of the outbreak, “Parents desert their children as soon as they are infected, and in every room you enter you see no person but a solitary black man or woman near the sick.” They cared for the infirm, many of whom were abandoned by loved ones who feared infection. They provided sympathy and comfort to confused children who watched with disbelief as their “asleep” mamma was carried out “in the box.” They were some of the first essential workers to hold society together in the midst of a widespread epidemic.

However, they didn’t receive the same applause as those who performed similar tasks early in the Covid-19 pandemic. Instead, they were slandered by a publisher named Matthew Carey.

Shortly after the outbreak ended Carey returned to Philadelphia – like most people who held his wealth and social standing, he left the city early in the fall. Carey’s first order of business upon his return was publishing a pamphlet titled, “A Short Account of the Malignant Fever, Lately Prevalent in Philadelphia.” In it he accused the Black population of profiteering on their services and of outright thievery from the homes where they assisted. His racist pamphlet sold so well that four editions were printed.

Allen and Jones felt the need to respond and correct the record. They did so in A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, During the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia in the Year 1793 and a Refutation of Some Censures, Thrown upon them in some late Publications. It was authored with only their initials, “A. J.” and “R. A.” In their narrative they described harrowing tales of physical and mental violence such as a white husband tossing his infected wife onto the street, threats of murder directed to those who were infected, and children orphaned without anyone to protect or care for them.

The Black population came to Philadelphia’s rescue during this crisis and held the city together. In the end, they were not immune. According to the statistics given by Allen and Jones, approximately one in six of Philadelphia’s Black population died during the four-month outbreak. Many of these people were infected while providing aid that most in society refused to perform. They died in service that was essential to Philadelphia’s survival.

Troy Tassier is a professor at Fordham University and the author of The Rich Flee and the Poor Take the Bus: How Our Unequal Society Fails Us during Outbreaks, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2024.