The History of Vaccines and the Importance of Vaccine Mandates

Part 2: Inoculation in the North American colonies and Washington's mandate

In 1706 a man with special knowledge arrived in Boston. The arrival had no fanfare. He had been kidnapped from his home in Africa, placed aboard a ship, and enslaved. Soon he was gifted to the Puritan minister of Boston’s famous North Church by members of the church’s congregation. This minister, Cotton Mather, renamed him Onesimus after another enslaved man mentioned in the Bible. It was Onesimus that brought knowledge of inoculation to North America.

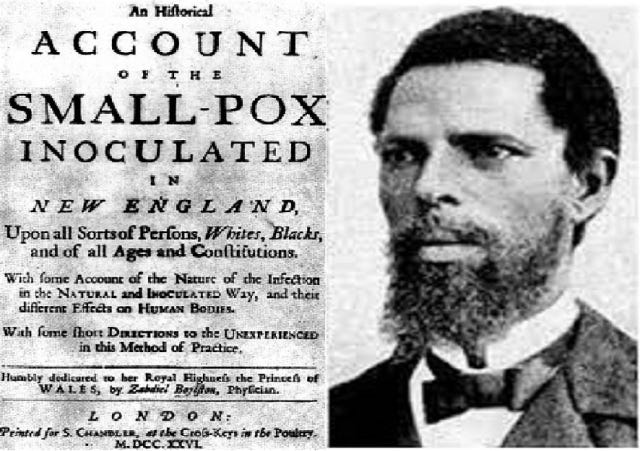

Onesimus

During a conversation Mather noticed a scar on Onesimus’ arm and inquired as to its origin. Onesimus described the procedure of variolation, where matter from smallpox lesions was placed in a small cut on the arm or leg of a non-infected person. He claimed that it kept him safe from disease. Mather consulted physicians in the area and learned more about the practice from others in England who had heard of the procedure too. When smallpox arrived in Boston in 1721 from a contaminated ship, the HMS Seahorse, Mather and a physician named Zabdiel Boylston inoculated their families and servants along with encouraging other Boston residents to be inoculated as well. To no surprise the recommendation was met with controversary. Racism was prominent and most Boston residents distrusted African medicine. In total only 247 people were inoculated. The practice was not without risk - two percent of this group died. However, fourteen percent of those naturally infected with smallpox died.

On net, the procedure saved lives, but concern mounted. How should citizens weigh the benefits and risks of the procedure? Were citizens more at risk from the procedure itself or from the possibility of natural infection and subsequent illness and death? Citizens from Boston and throughout the colonies fell to different sides of the debate.

Benjamin Franklin and Controversy in the Colonies

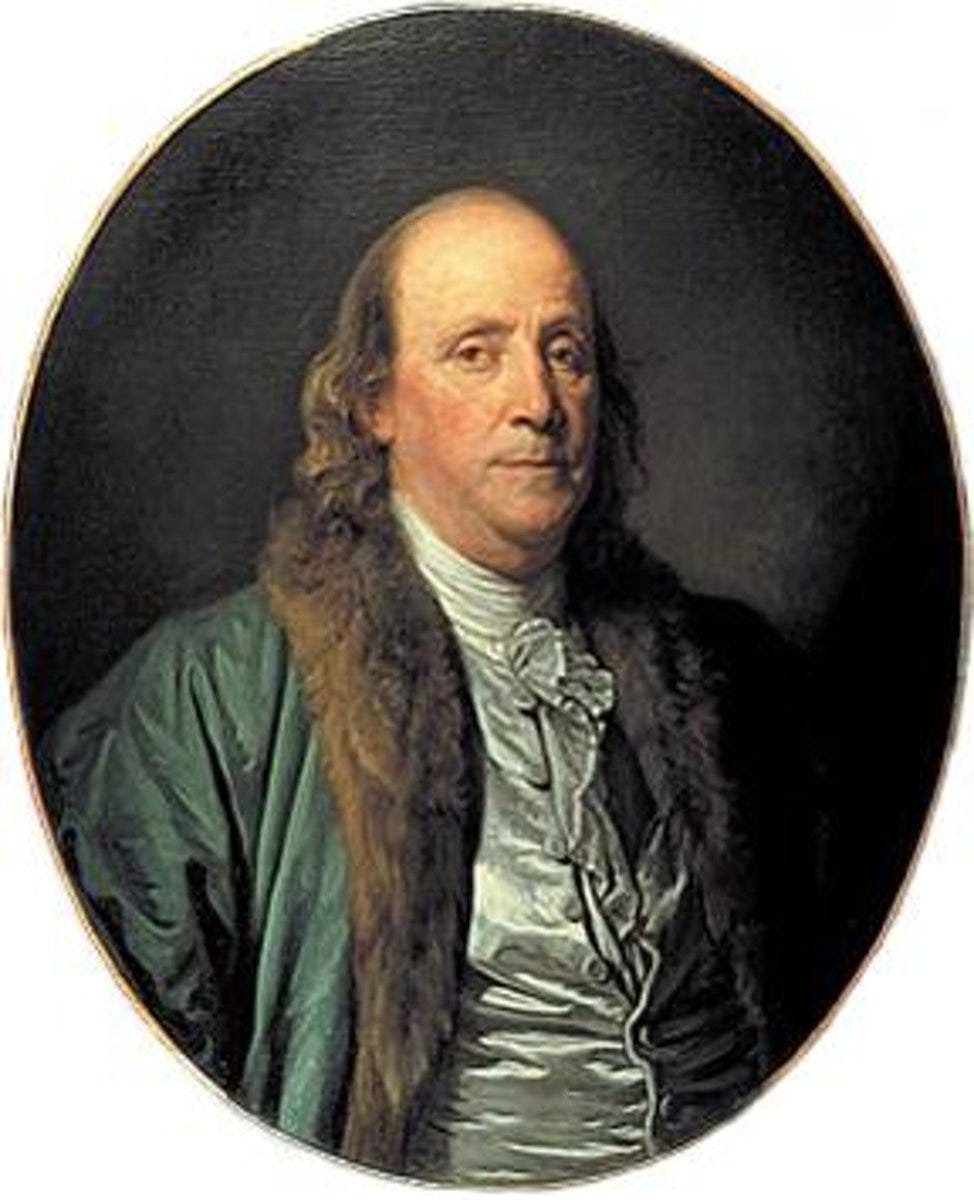

One who weighed the science carefully was Benjamin Franklin. At first Franklin opposed the procedure but he was won over following years of consideration. When his son Franky was born, Franklin intended to inoculate him. However, because his son was ill, Franklin postponed the procedure. He waited too long. Franky was infected and died of smallpox at the age of four. Franklin wrote in his autobiography, “In 1736, I lost one of my sons, a fine boy of four years old, by the small-pox, taken in the common way. I long regretted bitterly, and still regret that I had not given it to him by inoculation.”

The danger of inoculation in the early 18th century was not just about personal risk, however. Because the inoculated person suffered a (usually) mild case of smallpox, there was a chance that others could be infected by them and an outbreak could be seeded by the procedure. Because of this possibility many areas outlawed the practice. This brought about a great deal of turmoil throughout the colonies. Many common people wanted to undertake the procedure. But towns blocked them from doing so. As you might expect, an underground market developed. Many affluent and powerful members of society were able to circumvent the laws and be inoculated. This angered those who were unable to be inoculated or who were prosecuted for performing or undertaking the procedure. Riots occurred. Sometimes homes and hospitals were torched. (The controversy of the time is chronicled in Andrew Wehrman’s fabulous book: The Contagion of Liberty.) The events of this time period stand in contrast to today’s world. In colonial times citizens were protesting and rioting for the freedom to choose to be inoculated! The controversy continued when George Washington made a daring decision in the midst of the Revolutionary War.

"The Death of General Montgomery in the Attack on Quebec, December 31, 1775." John Trumbull, Yale University Art Gallery

The Revolution

At the start of the Revolutionary War the Continental Army had surprising success in the north. After moving through the wilderness of Vermont and capturing Montreal on November 13, 1775, General Richard Montgomery and Colonel Benedict Arnold set their sights upon the city of Quebec. A battle at the British fort ensued on December 31st that resulted in the death of Montgomery and a leg wound for Arnold. Little deterred, the siege continued into the spring. Then, in mid-May a smallpox epidemic broke out among the Continental troops and 1,800 of 7,000 troops died in a span of two weeks. While not a verified historical fact, rumors circulated that the British had sent infected people out of the fort to seed the outbreak as a weapon of war. Shortly thereafter, British reinforcements arrived and the Continental forces abandoned their efforts in Quebec. Of these events John Adams wrote, “Our misfortunes in Canada are enough to melt the heart of stone. … The smallpox is ten times more terrible than the British, Canadians, and Indians together. This was the cause of our precipitate retreat from Quebec. And, it has been claimed, the main cause of the preservation of Canada for the British Empire.”

The next year, partly upon reflection of this defeat, George Washington ordered the mass inoculation of all Continental troops. In the order to Dr. William Shipley he wrote, “Necessity not only authorizes but seems to require the measure, for should the disorder infect the Army … we should have more to dread from it, than from the sword of the enemy.” Washington’s decision brought forth the age of inoculation mandates.

By the end of the century a new more-safe method of inoculation would develop. Edward Jenner would call the method “vaccination.” He, along with Louis Pasteur and others in the 19th and 20th centuries, would advance this technology and set the stage for a series of medical marvels that would save billions of lives. The next article in this series examines their ingenuity and the public and political reaction to their inventions.

Troy Tassier is a professor of economics at Fordham University and the author of The Rich Flee and the Poor Take the Bus: How Our Unequal Society Fails Us during Outbreaks.

Part 1: Asia: The Earliest Inoculations

Part 2: Inoculation in the North American colonies and Washington’s mandate

Part 3: A Safer Procedure and the Rise of New Vaccinations

Part 4: Vaccine Inequality and the Case of Polio

Part 5: Measles Vaccines and the Importance of School Mandates Today