The Slippery Slope from Invisible Public Health to Visible Public Crisis

Public health contains a litany of great phrases, but this one is my favorite: “Public health is invisible until it fails.”

Public health keeps the food we eat and our children’s toys safe. It advocates for new norms of behavior such as increases in seat belt use and decreases in smoking. We expect to drink clean water, but then lead appears in the water pipes of Flint, Michigan and a crisis becomes all too visible and tragic. Many people don’t think about the role that public health plays in our daily lives until these types of safety measures fail and danger becomes visible.

The use of the measles vaccine displays another success of invisible public health. The recent outbreak that infected eight people in Philadelphia (six of whom were hospitalized) made national news. Another 200-plus person outbreak in England hit international airwaves. Before the measles vaccine, each of these would have been barely noticed as there were hundreds of thousands of infections and hundreds of deaths in just the US each year. This is the danger that invisible public health keeps at bay.

This weekend I happened across a tweet about a tool that helps to make visible the precarious nature of the safety that vaccines provide. It is a fun tool, but “fun” in the same way that a horror movie is fun. It uses a wealth of demographic data such as patterns of person-to-person interactions and commuting routes along with workplace and school locations to simulate what would happen if current measles vaccination rates dropped to 80%. You can pick a city of interest and watch a single case grow to an epidemic outbreak.

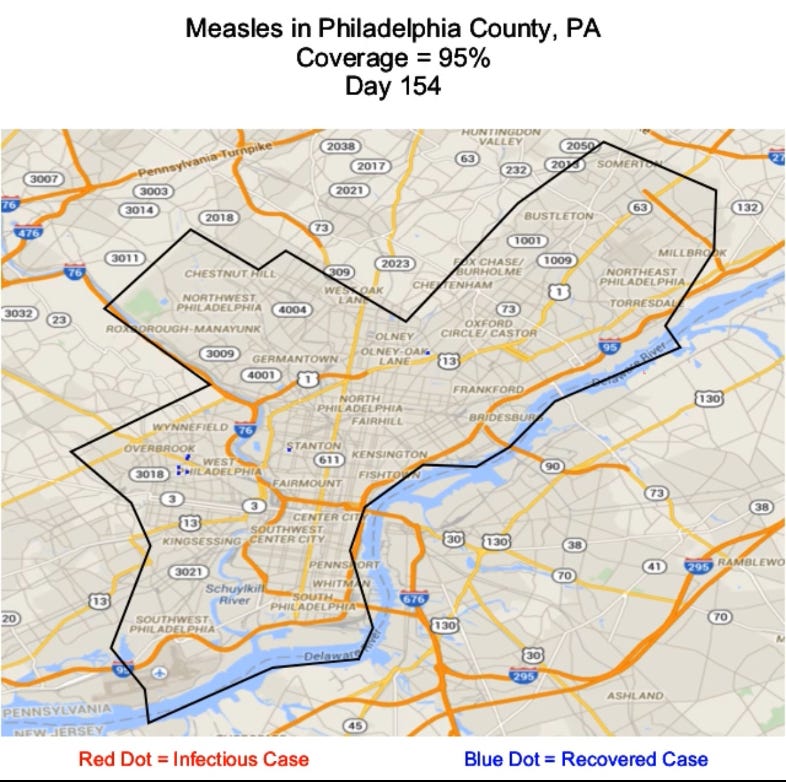

The first picture below displays the output for a measles outbreak in Philadelphia when the city has 95 percent of people vaccinated - a similar rate to the real-world measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine coverage in most US cities today. Finding the cases in this picture is a bit like asking “where’s Waldo?” If you look carefully, you will find seven little blue dots each representing one person infected and recovered. This looks much like the real-world outbreak that hit Philadelphia in recent weeks. While that outbreak made national news, this is still public health nearly invisible.

To make public health visible, you can simply look at the second picture. It displays an outbreak starting with the same initial case, but this time the city has just 80 percent of its residents vaccinated. You don’t need help searching for cases here. (If you want to try a city of your own choosing, the simulation tool can be found here, full citation given below.)

The present-day danger of an outbreak like this is closer than most realize. To the best of my knowledge, no city in the United States has MMR vaccination coverage this low. However, there are many individual schools and neighborhoods within cities that do.

A fabulous student of mine, Robert Betencourt, recently analyzed the distribution of the MMR vaccine across schools in California over the past two decades. In 2014 the state began phasing out eligibility for non-medical exemptions to their MMR vaccine requirement for children in schools and child care centers. When examining data just before non-medical exemptions were eliminated, Robert found that 20 percent of California private schools had less than 80 percent of their kindergarteners vaccinated. Further, 11 percent of schools had less than 70 percent coverage. One case in any of these schools would have sparked an outbreak and grown to the school-level equivalent of the second Philadelphia picture above. Instead of invisible public health, these schools sat with invisible public danger.

Today California is one of only 5 states that no longer allow non-medical exemptions to their vaccine requirements. The other 45 states that still allow non-medical exemptions probably look a lot like California in 2014 in terms of outbreak risk. Many schools in these other states sit with a danger that they and the parents of children in these schools do not realize.

Of course, the largest danger would occur if vaccination rates dropped this low across the entire country. Other areas of the world have faced this crisis recently. As I have written before, at the beginning of the century Ukraine had one of the highest rates of measles vaccination in the world. Once their MMR vaccination rate plummeted due to vaccine misinformation, measles cases surged to over 50,000 in two consecutive years. An outbreak of a similar per-capita rate in the U.S. would result in 350,000 infections, tens of thousands of hospitalizations, and, likely, hundreds of childhood deaths. Invisible public health can very quickly become invisible public danger. Once this happens, we’re just a spark away from a very visible real-world crisis.

Troy Tassier is a professor at Fordham University and the author of the forthcoming book, The Rich Flee and the Poor Take the Bus: How Our Unequal Society Fails Us during Outbreaks.

Citation for FRED simulation: Grefenstette JJ, Brown ST, Rosenfeld R, Depasse J, Stone NT, Cooley PC, Wheaton WD, Fyshe A, Galloway DD, Sriram A, Guclu H, Abraham T, Burke DS. FRED (A Framework for Reconstructing Epidemic Dynamics): An open-source software system for modeling infectious diseases and control strategies using census-based populations. BMC Public Health, 2013 Oct;13(1), 940. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-940. PubMed PMID: 24103508. Publication data.