Why the Gaines County, Texas measles outbreak is less unusual but signals more danger than most realize.

We’ve all been in a school lunch room. A large cavern of cacophony. Pots of sloppy Joes, trays of baked pasta, and those giant cans of peas and peaches doled out onto a plastic tray with a giant stainless steel spoon. Almost without error the scent from around the corner discloses the day’s menu even though it was often a mix of incongruent items.

I went to a small school but there were still fifty to one-hundred kids eating together every day. Kids, especially little ones, are “handsy.” They touch everything. And they roam, seat to seat and table to table, mixing and matching for most of the lunch period.

Imagine a virus enters the lunch room with these kids. It’s super contagious and has the ability to hang in the air for up to two hours. It infects kids with ease. Everyone present will be exposed over the course of twenty to thirty minutes. The kids who are infected will get sick. Some of them seriously. Around one in five will need to be hospitalized and pneumonia may set in. One in a thousand will die. Almost all who are infected will have a horrendous itchy rash that may leave them with scars. Of course, those of a certain age recognize this virus and the accompanying disease. Of course, it’s measles. It’s horrendous. Yet, those of us under a certain have never encountered it because of vaccines.

The Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) vaccine pops up in the news pretty continuously these days. Sometimes it’s a stray comment from RFK, jr. Other times it’s a public health professional lamenting our decrease in rates of vaccination among kids. At still other times, it’s a large, but preventable outbreak. Last year one in Philadelphia made the news. The year before it was Ohio. In 2019 the largest outbreak occurred in Brooklyn, New York which had over 600 cases of measles. This year, of course, it’s Gaines County, Texas. Here there have been over 300 cases and the number climbs each day.

This Texas outbreak and the death of an unvaccinated child, combined with RFK jr’s appointment to head HHS has had vaccines in the news even more than usual recently. Yet, for most, the outbreak in Texas seems distant and unique. It’s a small town community in rural Texas. Many of those who are unvaccinated and infected belong to a Mennonite community - even though their religious leaders do not openly oppose vaccines. Much has been made of the low vaccination rate within the county (around 82 percent) and of the even lower rate in some school systems within the county. Put all of these items together and it seems like an odd set of circumstances that are unlikely to be replicated in an area near you. However, there are many areas like Gaines County all across the country and they are growing in number.

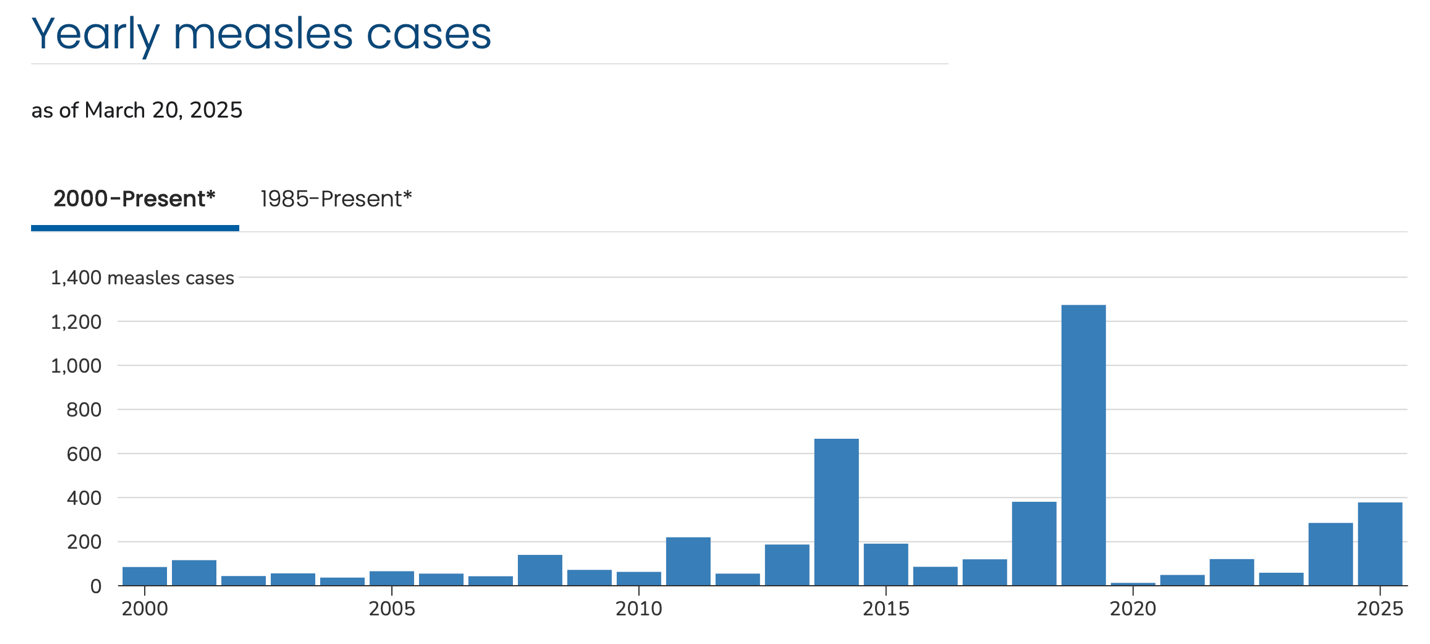

Figure 1: Data from CDC.

Measles outbreaks and cases in the US this century are on the uptick. Up until 2010 an outbreak like we had in Philadelphia last year or in Texas this year was rare. In the first decade of the century there wasn’t a single year with over 200 measles cases. We’ve had six such years since. Thus, in this sense, what’s happening in Texas isn’t that unusual – at least for the past fifteen years. However, it would have been very unusual twenty years ago.

Some who discuss this observation note the decrease in the overall vaccination rate across the country which has dropped by about two percent (from 95% to 93%) since 2010. Gaines County helps to reveal a more subtle and more important reason, however. Almost any average is made up of high and low values. Vaccination coverage is no different. For instance, in the US some states have much higher coverage than others. In 2011 the state with the lowest coverage was Colorado at 86.6%. In the most recent data, Idaho has the new low at 79.6%. The lowest values of coverage are getting lower. In addition, there are more lows as well. In 2011 there were only four states with coverage below 90%. Now we have 14 states below 90%.

Figure 2: Estimated coverage of state level MMR vaccination rates. Data from CDC.

Even though the coverage of some states is decreasing, the coverage in other states is increasing. For instance, Pennsylvania was one of the states below 90% coverage in 2011. Now, it has coverage of 93.5% - it’s above the national average. Overall the variance in coverage across locations, how coverage is spread between high and low rates, is increasing and this makes large outbreaks more likely.

Figure 3: Change in state level MMR coverage between 2011 and 2023. Data from CDC.

We see the same thing at more local levels. Counties in Texas look like a microcosm of the states in the US. Some Texas counties have decreased and others have increased. On average, the vaccination rate has dropped 5% across the state since 2011. However, in 2011 it had one of the highest state level rates in the country at 99.3. Today, it’s 94.3 percent. Much of this drop has occurred since the pandemic began in 2020. Still 94.3% is well above the national average. Yet, we can see a lot of danger across Texas if we look at the county level. We see a large number of counties with dangerously low coverage. (Those in the brightest red on the map.) I have highlighted Gaines County in the map below in blue. Just before the pandemic it had a coverage rate of 80.4%. Today it is still low, but has increased slightly to 82.8%. Our biggest problem with preventing outbreaks of measles are these low coverage counties and we are getting more and more of them as you can see on the maps below.

Figure 4: County level MMR coverage in Texas in 2019 and 2022. Data from the CDC.

Figure 5: Change in county level MMR cover in Texas. Data from CDC.

There are far more counties in Texas today that look like Gaines County than you’d expect. And, most importantly their numbers are growing.

In places like this, it only takes one case to spark an outbreak that results in hundreds or, potentially, thousands of cases. In a school lunch room filled with 100 kids from a community with an 80% coverage rate, there are 20 unprotected kids in each lunch period. If an infected kid enters that lunch room they will expose each of those 20 kids. And, they also expose the kids in the next lunch period and the next lunch period because of how long measles can linger in the air. We might end up with 60 or 80 or 100 kids exposed in just one day. Because measles is so contagious there’s a good chance that a very high number of those exposures will result in infections. Each of those infections brings measles into a home. Many of the siblings in these homes also will be unvaccinated. They can take the infection back to another school room, or friends in another grade. We get more and more cases. We get hospitalizations and even possibly a death like we had in Texas.

The danger of these low coverage communities should concern us more than overall aggregate trends in vaccination rates. We need to identify counties, communities, and school districts with exceptionally low vaccination rates. We need to reach parents in these areas and get their kids vaccinated before what happened in Gaines County becomes commonplace.

There’s another measure we can take as well. As I have argued before that we need to more stringently limit school exemptions to mandates for vaccines like MMR that have been proven safe and effective in study after study. As I demonstrated with data from California, where they tightened their exemption standards a decade ago, limiting exemptions greatly lessens the formation of low vaccine pockets like we see on the maps above. They keep our kids safe and prevent outbreaks like the one in Gaines County. And they can prevent the next outbreak which may be even worse.

Troy Tassier is a professor of economics at Fordham University and the author of The Rich Flee and the Poor Take the Bus: How Our Unequal Society Fails Us during Outbreaks.