How Deadly Were Gotham’s Tenements? Infectious Disease in the 19th Century (Part II)

This post is co-written with Rutger University - Newark professor of economics Jason Barr and published jointly on his Skynomics Blog.

“Prominent in the list of dangerous and aggressive nuisances are the tenement houses of the city….We thus speak of the inhabitants of the tenant-houses as constituting a class, and as being allied with the cause of sickness, pauperism, and crime.” New York Times, June 12, 1865.

Throughout the 19th century, New York City tenements garnered a reputation for vice, immorality, and, above all else, disease. As the above quote makes clear, most residents of tenement neighborhoods were lumped together and considered of equal nuisance. However, our previous blog post examined the risk of infectious disease mortality across Gotham’s wards during the height of tenement expansion from 1868-1910. We found something peculiar: some tenement neighborhoods had much lower infectious disease mortality rates than the citywide averages.

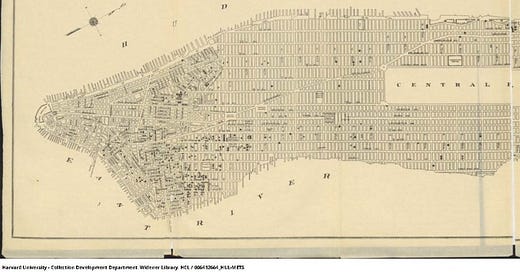

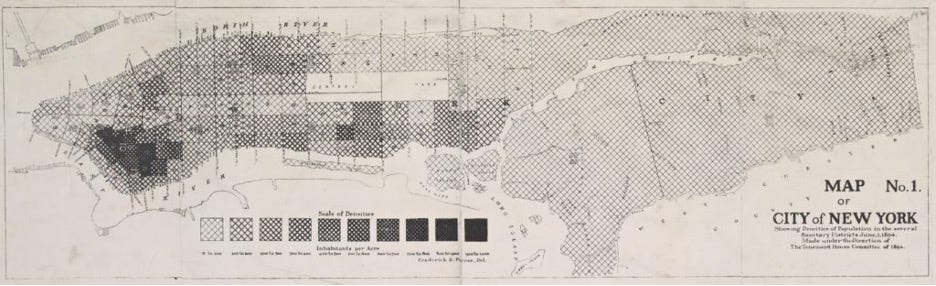

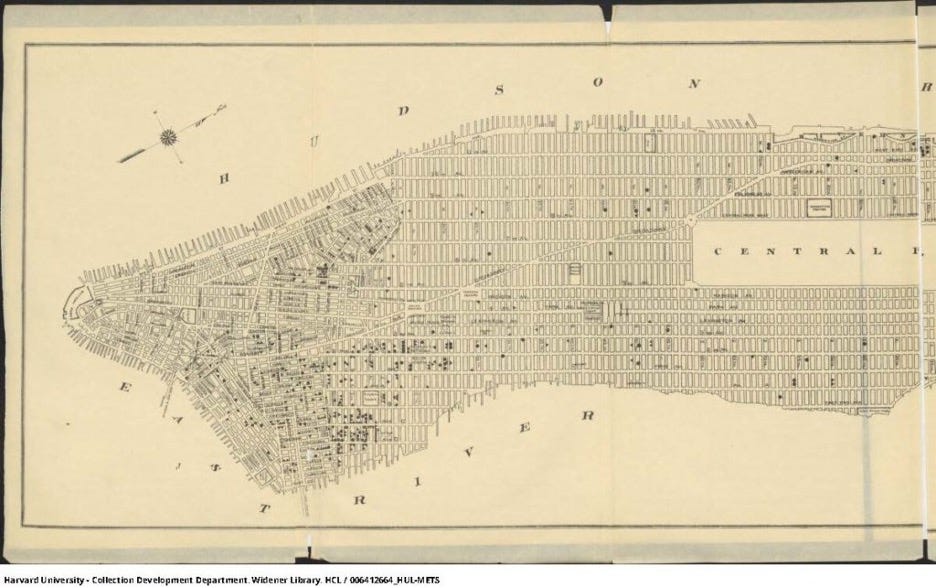

Figure 1: Density across Manhattan in 1895. Source NYPL Digital Collection.

In particular, the Lower East Side tenement wards were some of the safest in the city. On the other hand, more central and west-side tenement areas in lower Manhattan were among the most dangerous in terms of infectious disease mortality (see Figure 3 in Blog Post I). These differences beg the question: Why were some tenement areas relatively safe and others less so?

To begin the investigation, we plotted the rates of infectious disease mortality in the safe (Lower East Side) and less safe (risky) wards (Greenwich Village, Five Points, and the First and Fourth Wards) over time. The significant difference in risk began in the late 1880s. The decade from 1868-1878 saw minimal differences between these two regions. What was the same, and what was different about these wards? The short answer: it’s complicated!

Figure 2: Death Rates from Infectious Disease in Safer Tenement Wards vs. Riskier Wards. Note: The red line is the long-term city average (0.95%) from 1868-1910. Safe wards: 7, 10, 11, 13, 17. Risky wards: 1, 4, 6, 14. Source: here. For ward map see here.

Which of these things is not like the other?

Let’s review the possible hypotheses and see what the data suggest.

Tenement Concentration

At the beginning of our period, the 1870 census reveals that each group had about the same share of tenement homes, around 65 percent. Thus, each contained about 20 percent more tenements than the city-wide average. By 1900, New York’s explosive population growth led to a skyrocketing share of tenement dependence, with approximately 75 percent of all Manhattan residential units in tenements. (Data sources and analyses are here).

The safer wards closely matched this average, while the risky wards had a slightly higher share than the citywide average. Given that tenements were used citywide to house most residents, the presence of tenements in and of itself did not make one area riskier than another.

Density

Differing population density provides another possibility for the differences in mortality. Concentrating people increases the chances that an outbreak will spread quickly. However, density doesn't fully explain the observed mortality difference. The safer wards were far denser than the risky wards. We can see the hyper-density of the Lower East Side (LES) tenements in the above map from the 1895 Tenement-House Committee.

In particular, the Tenth Ward had over 650 people per acre in 1900. All the wards in the safe grouping had at least 430 people per acre. On the other hand, the densest risky ward, the Fourteenth, had only 315 people per acre. All the other risky wards had under 235 people per acre. In short, the difference in mortality was not due to density.

Average Wealth

Wealth provides another potential reason for the difference in risk. Historically, more impoverished areas tended to be harmed the most during epidemic outbreaks. Other than the First Ward (which was wealthier per capita), the riskier wards had personal property per capita near the city median of $82 and real property per capita lower than or near the city median of $947 per capita. These wards were far from wealthy. However, the safer wards were even less affluent, on average. The LES Tenth, Eleventh, and Thirteenth Wards were the most impoverished of the city in terms of median wealth per capita—yet they had much lower infectious disease mortality.

Dampness and Poor Ecology

Could ecology and topography provide an answer? Damp areas and former marshes pre-European settlement might provide more fertile ground for disease than higher ground with better drainage, particularly for cholera and other waterborne diseases. We considered various possibilities, such as former marshlands, the presence of streams and other water sources, and the presence of Oak Tulip trees that grew on hillsides, where drainage was good. Again, none of these lead to a clear difference. In some areas, land conducive to the spread of infectious disease is associated with minimal mortality. Other sites that had a favorable environment had high rates of mortality.

In summary, most of the things that we associate as potential and obvious risk factors for infectious disease do not, in fact, correlate well with the different levels of infectious disease mortality. However, other differences stand out and begin to reveal the story of what was determining tenement health.

So, What’s the Answer?

To begin, we must step back and examine the bigger picture of change in the city. Manhattan's population grew rapidly during this time. Between 1870 and 1910, the population increased by nearly 250 percent, from 942,000 to 2,330,000. Part of this increase occurred in the northern wards that were previously underdeveloped. The population of the Twelfth Ward (the northernmost and largest ward in terms of land area) grew by an astounding factor of 28. This was partly due to its minuscule population as of 1870 and its sheer size.

The city's median ward saw its population increase by 26%. However, growth was very uneven across the island. Several southern wards, including three tenement wards in the risky group, saw population declines.

These three tenement wards stood in stark contrast to the safer tenement wards, each with a population that doubled (or more) between 1870 and 1910. This growth led to a sharp difference in density in this area compared to the other neighborhoods. This sharp rise in population and density would be expected to lead to more disease and not less. So, what happened? The explosive growth led to new construction in the area. These newly erected tenements met requirements that reformers put in place to keep the population safer from disease..

Enter Tenement Laws

As the population of Manhattan exploded, reformers worried about dangers of tenements. By all accounts, some dwellings were beyond horrible. The New York Times wrote of basements and backyards filled with sewage that drained into first-floor apartments. Interior rooms and entire apartments had no light or windows. Households with seven or more people lived in 6-foot by 7-foot rooms without space for everyone to sleep at once. Because of these poor living conditions, reformers called for action. As chronicled in the New York Times in 1865:

“The fact is that the population of the city has become alarmingly great, and unless some attention is paid to its sanitary condition we shall be forced by the grim monster itself to bow down in dust and ashes of bereavement…. Is there a responsibility nowhere? Cannot something be done by the people, which will compel authorities to root out such abominations, remove such nuisances, and thus do much toward redeeming the children from lives of infamy, misery, and pollution?”

In response, New York City passed a series of reforms to improve the safety of tenement buildings. The First Tenement Act of 1867 required a fire escape for each dwelling and a window for every room. The windows were intended to provide fresh air, ventilation, and light. However, many newly built apartments were compliant simply by installing a window to an interior hallway, which did little to improve ventilation.

Figure 3: Left: A Rooftop View of Two Dumbbell Tenement Shafts. Right: The Bottom of a Shaft. Sources: Left: Wikipedia. Right: Report of the Tenement House Department of the City of New York 1902/1903.

The Dumbbell

A series of additional acts improved conditions further and closed many loopholes. In 1879, windows were required to face a source of fresh air and light—not a hallway. Yet this, too, was met by developers with minimal compliance. Many newly built tenements simply added a narrow gap between buildings. This new building style became known as the dumbbell tenement after an 1879 competition meant to generate fresh ideas for tenement designs.

Developers typically erected this style of tenement stacked next to each other with only the narrow air shaft closed on each end, separating them as seen in the picture above. While this improved ventilation somewhat, later laws created more improvements. However, there was a problem with the dumbbell. Many buildings were not yet connected to sewers, and tenants could dump human waste and other garbage out of apartment windows into the narrow gap between buildings, creating new health problems. This was partly corrected in 1887 when each building was required to have an interior privy.

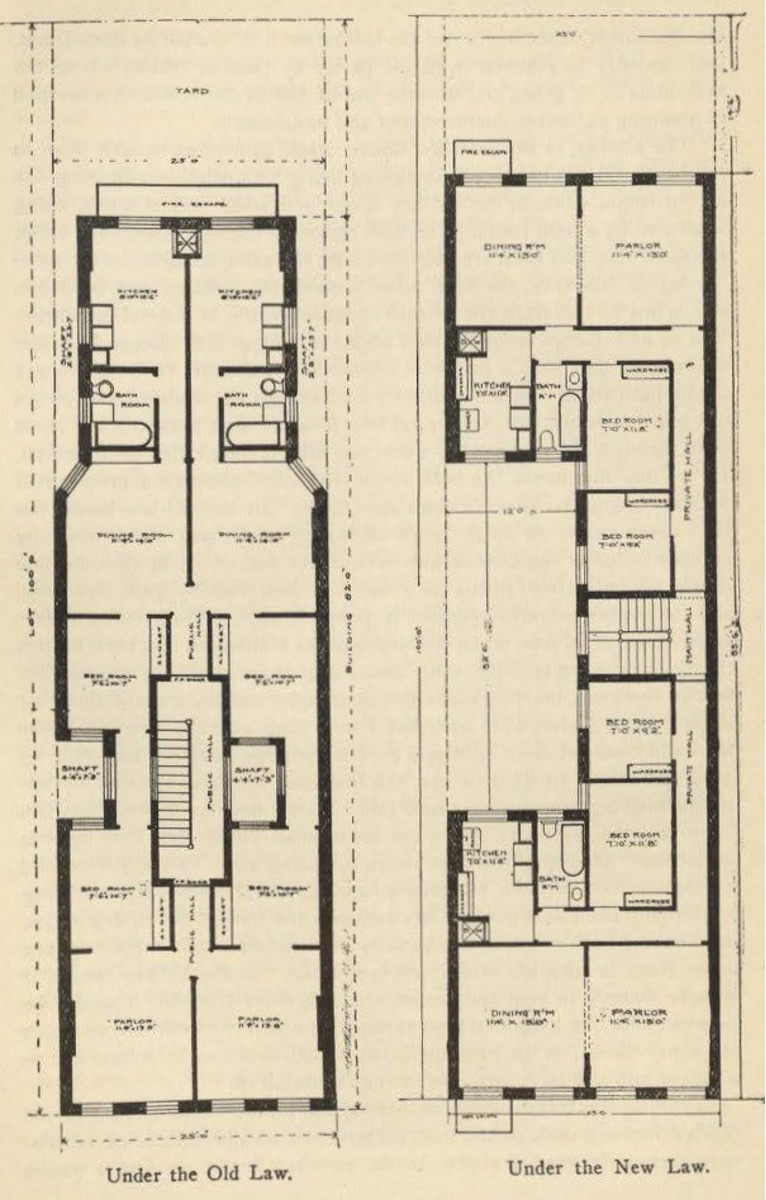

Figure 4: Two Tenement Plans. Left: A tenement that met the ventilation requirements of the pre-1901 laws. Right: A "new law" (1901) tenement plan that met the courtyard ventilation requirement. Source: Report of The Tenement House Department of the City of New York 1902/1903.

The New Law

Finally, in 1901, stricter and more comprehensive standards were established. New requirements ensured better lighting in hallways. Most importantly, indoor bathrooms were mandatory, and each tenement needed a large courtyard. The last requirement ensured ventilation because each room now had a window that opened onto the courtyard, a street, or the backyard. Most of these “new law” tenements were built in areas with the largest growth. These were the areas with the lowest infectious disease mortality in the city.

Safety with Growth

Data on new buildings and compliance with tenement laws is less available than data on infectious diseases. However, from the available data, the safer wards, which had higher rates of growth, were constructing more new tenements as the laws evolved to ensure more safety. This is also the time during which we observe the difference in infectious disease mortality in the two ward groupings.

For example, from an 1891 New York City Department of Health report, we found that the safe wards had 144 instances where building plans were filed for plumbing and drainage that year. The risky wards only had 16. A similar report in 1891 documents filings concerning light and ventilation. There were 152 filings for new building plans in the safe wards and 25 in the risky wards. From these data, it appears that by the 1890s, more new tenements were being constructed in the safer wards. This period falls shortly after the second generation of tenement laws were enacted.

We also can get a sense of the rate of new construction by looking at the total number of existing tenements in each ward in years where this data is available. In 1896, the safer wards contained 193 more tenements than in 1892. The number of tenements in the riskier wards increased by only 67 in these four years. Though we can't directly ascertain building ages or compliance with the laws, certainly some buildings were torn down and replaced with improved and safer structures. The data gives us a sense that the safer group of wards had newer building stock that met the safer building codes of various tenement acts. Compliance with these more recent reforms likely made the Lower East Side Wards safer.

Additional evidence comes from reports of new tenement construction in tenement districts after 1901. The report's maps show that far more new tenements were built in the safer wards.

Figure 5: New Law Tenements Erected between January 1902 and July 1903. Dots represent 1902 construction and triangles represent 1903 construction. The majority of new tenements during this time period were built in the safer wards. Source: Report of The Tenement House Department of the City of New York 1902/1903.

Rear Tenements

The 1900 tenement house census gives us another glimpse of the age and quality of the building stock by counting the number of rear tenements in each ward. Rear tenements were additions located in the back alleys of tenement neighborhoods. Many were ramshackle dwellings that were even more spartan than the typical tenement buildings you see in movies or on a tour at the New York City Tenement Museum.

In most cases, rear tenements were the lowest form of shelter in the city. Sometimes, they were built purposely as residences. Other times, they were converted sheds or sometimes even old outhouses. Generally speaking, they were not the four- or five-story stone and brick structures that most envision when considering New York City tenement houses. The number of rear tenements in the risky Fourth and Sixth Wards was far higher than in any other ward of the city—nearly one in four. Again, this leads one to believe that the building stock in the risky wards was older than in the safer wards.

Figure 6: Two Photos of Rear Tenements in late 19thCentury Manhattan. Note the traditional tenement buildings sit in the background of each photo. Source: Jacob Riis's 1890 book, How the Other Half Lives: Studies among the Tenements of New York. Images from here.

From whence They Came

The final significant distinction between these two groups of tenement wards concerns the place of origin of the respective tenement populations. As of 1900, each risky ward contained between 61% (1st Ward) and 78% (4th Ward) Irish or Italian immigrants. The Irish fleeing famine in the mid-19th century likely had little of monetary value upon arrival. While many immigrants from other locations certainly lacked wealth, they presumably were not as destitute on arrival as the Irish famine refugees.

On the other hand, the safer ward groupings contained populations overwhelmingly from Eastern Europe. Each of these wards had at least 75% of its population originating from Russia, Poland, Germany, or the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Many immigrants were Jews escaping discrimination and persecution. While they may not have been wealthy upon arrival, many were likely not as poor as those who settled in places like Five Points.

Reform for the Win

Putting all of these factors together, a picture begins to emerge. The riskier wards likely had older, less sanitary, and less safe dwellings concerning infectious disease risk. Because of their earlier reputation as bastions of infectious disease, they were likely avoided by all with the financial means to do so.

At the same time, other Irish and Italian neighborhoods emerged farther north in the city. The Fifteenth Ward, discussed in the previous post, contained just over 50 percent of residents with Irish or Italian heritage. So did the 21st Ward just to the south of present-day Grand Central Terminal. Other areas throughout the city had significant Irish and Italian immigrant populations where people with relatively higher incomes could settle. The fact that some people remained in the most disease-ridden area of the city in older, decrepit housing likely indicates that these people didn't have the financial means to escape to anywhere better.

On the other hand, the safer Lower East Side tenements likely contained newer buildings that were more sanitary and included more ventilation and light. It wasn't that these areas were wealthy–far from it–but the living conditions and newer building stock likely allowed the people who settled there to avoid at least some risk from infectious disease mortality.[1]

Reevaluating Death and Disease in the Tenements

While New York City's 19th-century tenement neighborhoods received a bad reputation for high infectious disease rates, there is far more nuance than the folklore suggests. Disease was part and parcel citywide in the 19th and early 20thcenturies. No area, rich or poor, tenement or not, was spared from infectious disease risk. Yes, some tenement areas were particularly dangerous, but not all. Likely, the evolving tenement reforms of the late 19th and early 20th centuries created safer conditions in the tenement districts that saw the most population growth and new construction of safer buildings.

You can read Part I of the blog post series here.

Jason Barr is a professor of economics at Rutgers University-Newark. He is the author of Building the Skyline: The Birth and Growth of Manhattan’s Skyscrapers. His latest book, Cities in the Sky: The Quest for the World’s Tallest Skyscrapers, will be published in May 2014. He also writes the Skynomics Blog, a blog about skyscrapers, cities, and economics.

Troy Tassier is a professor of economics at Fordham University. He is the author of the forthcoming book, The Rich Flee and the Poor Take the Bus: How Our Unequal Society Fails Us During Outbreaks.

---

[1] One can also understand how these wards might have earned an undeserved reputation simply because of their density. With so many people living in these areas, even an average level of infectious disease would stand out in absolute numbers. If two wards each had one percent of their population die during an infectious disease outbreak but one of the wards contained five times the density compared to the other, the denser ward would have five times the number of deaths. Thus, if newspapers and other sources of information simply report stories about the number of casualties, the denser areas will garner a more dangerous reputation that they don’t deserve simply because of the sheer number of deaths.