Look Up (and Outside)

We need to see the pandemic.

Recently Sharon Otterman wrote an article in the New York Times about the pandemic titled, “900,000 New Yorkers lost at least three loved ones to COVID.” These words state the punchline for the article and summarize a key point from the recent New York City Housing and Vacancy Survey. Most who lived in the NYC metro area during the spring of 2020 will not find this number surprising. Many others from outside New York City who experienced the pandemic first hand will not be surprised either. Most of these people know at least someone who lost a loved one to the pandemic. Yet there are people from other areas of the country who will scoff at the findings in part because they haven’t looked outside of their personal circumstances to see the toll of pandemic harm that others faced and continue to face.

The instinct to look inward at our own circumstances of the moment is reminiscent of the 2021 academy award winning movie “Don’t Look Up.” In it, two astronomers, played by Jennifer Lawrence and Leonardo DiCaprio, attempt to warn the world of a massive asteroid hurtling toward the extinction of Earth. They encounter various attempts by politicians, the media, and the general public to obfuscate the news of impending doom. Ignorance is bliss and no one wants to see what could come. It would be inconvenient to do so. The movie has intentional parallels to the climate crisis and perhaps the ongoing pandemic. Yet, it is clear that many have not taken the message forward and many fail to look at the pandemic in 2023.

When we do look across the country there is great variance in the concentration of pandemic harm. Some areas suffered, and are still suffering, far more morbidity and mortality than other areas. Overall to date, the United States has lost more than 1.1 million people to the pandemic - this equates to about 350 people per 100,000 US residents who have died as a result of Covid-19. (Excess death analysis suggests an even larger toll.) If we separate all of these deaths according to the county of residence at death, we begin to see the different experiences of the pandemic. While the average across the United States is 350 deaths per 100,000 people, some counties have over 1,000 deaths per 100,000 people. In these counties more than one percent of the population has died due to Covid-19. At the other end of the distribution, a small number of counties have reported no deaths from Covid-19 and 96 of the 3,142 counties in the US have fewer than 100 deaths per 100,000 people. Some counties have three times more deaths per capita compared to the average and some counties have three times fewer.

Figure 1. The distribution of rates of death across counties in the United States.

Figure 2: Underlying data from USA Facts. Map produced by author.

One can see on a map how these discrepancies are located across the geography of country. The map is patchy. Some areas, particularly those in the rural south and the north central parts of the US have much higher rates of death per capita than the average county in the country. Of course, Covid-19 is everywhere but it is more concentrated in some areas than others. To get a more precise sense of how this data is distributed, we can turn to some simple statistics and an old economist in his garden.

In the early 20th century, legend holds that Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto observed a set of pea plants in his garden and noted something curious. A few of his pea plants produced the overwhelming majority of the peas while most plants produced only a few. He began counting the peas produced from each plant and found that 20-percent of the plants produced about 80-percent of the peas. This finding set Pareto on course to study other forms of uneven distribution. Most famously he found that about 80-percent of the land in Italy was owned by only 20-percent of land holders. Other uneven distributions have been found in income, wealth, and a host of other economic variables. Unequal distributions are often found in health outcomes and many other areas as well.

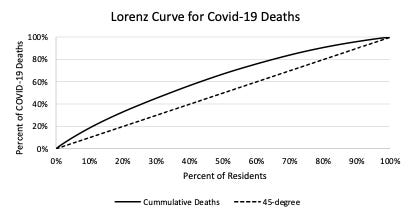

The Lorenz curve, named for economist Max Lorenz, presents a way to easily observe the magnitude of unequal distributions such as those observed by Pareto. To create a Lorenz curve for a health variable, such as Covid-19 deaths across counties, we order the counties from those experiencing the most deaths per capita to those experiencing the least. We then plot the cumulative percentage of the population living in the counties and the corresponding cumulative percentage of Covid-19 deaths. When you do this for all counties you arrive at the following graph.

Figure 3. The curve presents the percent of the US population that produces a corresponding percentage of Covid-19 deaths.

To read the graph, choose a percentage of the US population and look to see what percent of deaths occurred in that portion of the population. For instance, 10-percent of the US population lives in the counties that have produced 18-percent of the Covid-19 deaths. Counties containing 20-percent of the population have produced 33-percent of the Covid-19 deaths. Counties that make up 30-percent of the population have 45-percent of the Covid-19 deaths. These counties suffer disproportionately.

For a comparison, suppose that we have a variable that is evenly distributed across all US counties. What would that variable look like if plotted as a Lorenz curve? Ten-percent of the population would produce about ten percent of the incidence. Twenty-percent of the population would produce twenty percent. For instance, consider the distribution of women (or men) across US counties. This distribution is much more equal than Covid-19 deaths. Most counties have nearly a 50-50 mix of women and men. A distribution like this produces a Lorenz curve that falls almost perfectly on the 45-degree line.

Figure 4. The curve presents the percent of the US population across counties that includes a corresponding percentage of women.

Lorenz curves that have more “bend” to them, like the Covid-19 death curve, indicate more inequality in the underlying distribution. One can condense the information from a Lorenz curve to a single number by measuring the area between the curve and the 45-degree line. More area between the two curves indicates more inequality. Economists refer to this area as the Gini coefficient of inequality, named after the Italian statistician and sociologist, Corrado Gini. A larger Gini coefficient means that there is more inequality in the distribution.

For Covid-19 deaths the Gini coefficient is 0.24. How much inequality is this? By itself, this number means little. So let us compare it to something that may be more familiar, poverty.

Figure 5. The Lorenz curve for poverty in the US.

Figure 6: Map of county level poverty rates across the US.

The Lorenz curves for poverty and Covid-19 deaths look very similar. So does the patchiness of their maps. The Gini coefficient for poverty is about 0.20. Covid-19 deaths are distributed more unequally than poverty but not by much. Now, to be clear, the similarity of the two Gini coefficients does not mean that the distributions are the same or that the location of concentration is the same. It only means that the distributions of poverty and Covid-19 deaths contain similar amounts of inequality.

Now we can come back to the beginning. For some people in the US it is not surprising to say that they know multiple close friends or relatives who died from COVID-19. Just as it is not unusual for some people to say that they know multiple people who live in poverty. Similarly, some people know no one who lives in poverty or no one who died from COVID-19. The discrepancy occurs in part because both of these things are more concentrated in some geographic areas and not in others. Poverty exists everywhere and COVID-19 deaths occur everywhere. However, each are concentrated most strongly in particular locations.

In this case, there is a significant amount of overlap in the areas of the country struck most severely by Covid-19 deaths and the areas where poverty is concentrated. The 10-percent of counties that have the most Covid-19 deaths per capita have an average rate of poverty of 20-percent. This is nearly twice the national average. In these same counties, 29-percent of children live in poverty. Because Covid-19 deaths are concentrated here these children are more likely than affluent children to lose a parent, grandparent, or other caregiver. They will carry this trauma with them for their lives no matter how their financial circumstances change or don’t change. This trauma will affect their education and everything else about their lives.

The same counties have high rates of overcrowded housing. Overcrowded housing allows viruses to spread more easily and leads to more infections. Further, these counties have higher rates of uninsured individuals and those that are insured but live in or near poverty often have lower quality insurance plans. Whether insured or uninsured, people in low income areas often receive lower quality health care. The counties with the most Covid-19 deaths per capita also score lower on measures of food security which is calculated by considering access to affordable and nutritious food sources. Areas that lack food security are termed food deserts. Both lack of access to high quality health care and living within food deserts lead to worse overall health and higher rates of co-morbidities before a pandemic arrives. In turn these lead to more severe health outcomes and deaths from infections within a pandemic.

The concentration of an epidemic outbreak in a disadvantaged area is not unique to our time or to Covid-19. In New York City, the 19th century cholera outbreaks wreaked the most havoc in notorious poverty-filled neighborhoods like Five Points and other lower east side tenement blocks. After the initial polio vaccines became available in the early 1950s, polio became concentrated in impoverished rural and inner-city neighborhoods and continued to disable and kill children and adults who resided in these neighborhoods. The HIV/AIDS epidemic migrated to become concentrated in rural and urban Black populations (as recounted in Jacob Levenson’s excellent book, The Secret Epidemic). Across the world millions die every year from AIDS, malaria and TB – the majority of these deaths occur in the world’s most impoverished areas. The list linking epidemics to poverty goes on and on.

Many don’t see these historical and present day epidemics through the lens of class privilege. They may not see or think of them at all. Similarly, they don’t see the Covid-19 pandemic as a risk to them today in part because they live in more financially secure environments. They live with more safety from infection and more resources if infected. They are people who can isolate at home when danger is near and who can seek high quality medical care when needed. Some have termed these people the “laptop class” of society who look around their homes and neighborhoods and see little risk from the ongoing pandemic. No one they know is seriously ill. None of their friends is dying or hospitalized. Their loved ones are all safe. They don’t look deep enough beyond their myopic day-to-day gaze to see the circumstances of those less fortunate. They don’t look at how their circumstances differ from others. They don’t look up and outside of their own community.

The pandemic causes the most harm beyond their everyday perception. Many of these people want to return to normal lives and ignore the plight of others who still live in pandemic circumstances with high rates of morbidity and mortality. As I wrote in May, the most severely imperiled areas of the US are still living through the pandemic in circumstances little different than our worst fears from spring 2020. Yet, the more privileged areas of the country and the vast majority of our political leaders want to move on as though the current pandemic has disappeared entirely. As Yale epidemiologist Gregg Gonsalves recently wrote in the Nation: “the ‘urgency of normal’ is about class and race privilege, … putting the pandemic ‘behind us’ is really about making things easier for people with money and good health insurance who think they can pop some Paxlovid, sit in bed with their laptops propped up beside them if they get sick, and power through it all like it was ‘just the flu.’” It isn’t just the flu for so many who have the fewest advantages in our society. Yet, many don’t see them because they don’t look.

Many walk past an unhoused person in the street without making eye contact or thinking about their circumstances or what brought them to the street. These people who avert their eyes on the street also don’t look at the ongoing pandemic. Instead of looking away, we need to see the turmoil that the pandemic still causes across our country. When we look away, we are complicit in the harm that is caused. We can’t look away just to ease our minds or to live a life of convenience without guilt. We need to see the ongoing pandemic and accept our part in the turmoil that it continues to cause in our society. We need to look up and see that the pandemic is still amongst us especially among our least fortunate members of society who need our help the most.